Stay 731: Geography

My first semester of graduate school in Greensboro, North Carolina, the main thing I remember about poetry workshop—besides the necessity of snacks to feed the muse—was a diagram that my professor drew on the whiteboard one afternoon.

Becca wrote WHAT THE POEM IS ABOUT above two intersecting arrows. Then, she labeled each end of the arrows. Viewed as a compass, the west represented the start of the writing process; the east represented the end of the writing process. North represented the public aspects of writing; south represented the private aspects.

There was some talk of GUILT. Guilt over feelings in poems. The guilt of not saying something well enough in a poem, after all the drafts. The guilt that comes with asking, “Do I have the right to say ________?”

Sometimes it’s helpful to have someone show us a means of navigation. I’ve been thinking about those arrows, about the geography of writing.

When I moved from Jackson to Greensboro the summer of 2013, I thought I was leaving Jackson for good. I closed doors and packed boxes, took photographs, ate last meals. Familiar gestures for someone raised with a passport in her hand, someone whose least favorite small talk question is, Where are you from?

When I left Jackson, it traveled with me. Seventy percent of my graduate thesis was poetry inspired by or directly about people and events in West Tennessee.

Of course, you say. Aren’t writers allowed to write about what they know?

Despite having family from here, despite growing up near the city for a time, despite returning for college, despite jobs, despite downtown and midtown, despite failure, despite the short turbulence of spring, there’s a lot I still can’t wrap my mind around.

During my two years in Greensboro, I often never knew precisely what drove me to the page, except for the basic requirement of workshop: turn in a poem a week. Some form of guilt would rise to the surface of each poem I turned in because the perfectionist in me said, Not enough.

But remember the diagram, the arrows? They intersect. Not only do they cross, they continue. Eventually I learned instead of trying to place a finger on why, I kept writing, kept throwing words at a page and hoping they stuck.

When I wrote poems concerning darkrooms and photography, farms, grandparents, siblings, tornados, death, abduction, and going to church, I was trying to name a landscape, a particular stretch of Bermuda grass, dogwoods, kudzu, and red clay off I-40.

Or: that place means memory, that memory means a pattern, that a pattern means something we can trace, something we can hold.

I don’t know whom I’m writing this piece to specifically, and that might be a problem. I don’t know who needs to hear my words the most, or who needs to hear my words at all. I’m not sure what I’m supposed to say here, other than that it seems that leaving Jackson gave me the means to understand her better.

In my case, the act of staying has been the act of returning. Each time I’ve returned, I see more and more.

I see how this time, I cannot walk from my house on Wisdom Street to my maternal grandparents’ house on the corner of Omar and Waverly. It’s not their house anymore.

What I mean is this: I walk past the house; try to get a glimpse of the backyard shaded by the neighbor’s giant pin oak. I spent summers in that yard sprawled on a cheap plastic lounge chair, reading. I can point to the exact spot where I read Charles Wright’s lines in “Apologia Pro Vita Sua,” from his collection, Black Zodiac:

Landscape's a lever of transcendence—

jack-wedge it here,

Or here, and step back,

Heave, and a light, a little light, will nimbus your going forth…

Whether I’m back in Jackson for the next six months, six years, or six decades, I’m mostly interested in what I’m going to write next. Not why. I leave the why for someone else to pick up, move along.

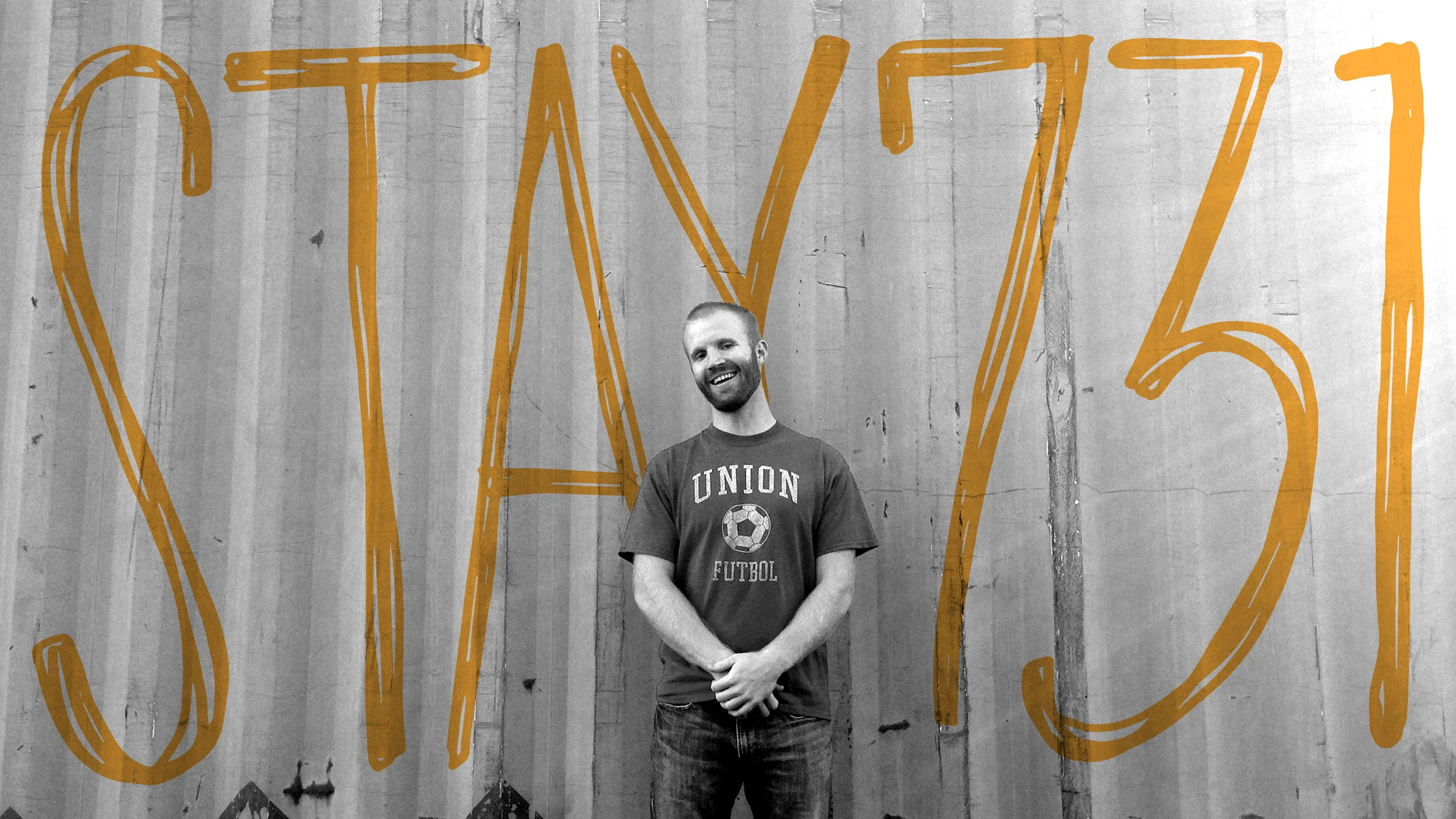

Lauren Smothers is a recent graduate of the MFA program in creative writing from The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. In August of this year, she moved back to Jackson. She teaches composition and literature at Union University.