Green and Gold Again

BY GABE HART

FEATURED IN VOL 7, ISSUE 2: Legacy

Our memories are fickle. They seem to attach themselves indiscriminately to the films that run on a loop through our brains. What starts as entire scenes from our pasts are eventually whittled down to vague clips that may only last a second or two — like tiny shells at the bottom of a sand sifter.

I have a few of these scenes that will flash through my mind sporadically. My first hit in Little League at Lions Field — the ball looping in the air and landing in front of the center fielder. Sledding down Snake Hill on my father’s back when I was young; taking that turn at warp speed and ending up in Westwood Gardens. My first day of high school at Jackson Central-Merry — the sun just breaking from the east over Lane College and straining my eyes to see how far the crosswalk stretched before it dipped beyond North Royal. That scene in particular is in my life’s movie. It made it beyond the cutting room floor.

The first day of high school is most likely a memory that sticks with most people. It is a day filled with nervous excitement along with fear, and fear during adolescence is essentially an emotional adhesive, binding memories permanently. Remembering the first day of high school isn’t that uncommon. Remembering the first day at JCM, however, is something that can only be understood if you were a Cougar. To borrow a phrase of a JKSN grown, JCM alum, Cliff Martin: “If you know, you know.”

As soon as I stepped out of my mom’s GMC Safari Minivan on that August day in 1993, I looked as far as I could toward the east and saw the crosswalk disappear. My immediate thought: “I’m never going to figure this out.”

I did figure it out, though, and four years later in the spring of 1997 I turned out of the Oman Arena parking lot for the last time with “Number 41” by Dave Matthews playing in my Nissan Maxima, not knowing what a truly special school JCM turned out to be.

Over the last quarter of a century, I have tried to explain what JCM was like to people I know who are from Jackson or grew up out of town. I find that when I tell them about state championship athletic teams or Ivy League graduates I hear my own words not making sense to me. When I tell them about a racially diverse school of over 2,000 students that offered AP classes and rigorous honors classes, I regret that I didn’t appreciate what my high school was when I attended. When I choose stories to read with my middle school English class that I once read as a student at JCM, it is the best way I know how to honor the truly outstanding English department that shaped my love for reading in high school.

My JCM story, however, is only a snapshot. My time there is a lot like those indiscriminate memories that hang around our heads — short and unimportant in the context of the narrative.

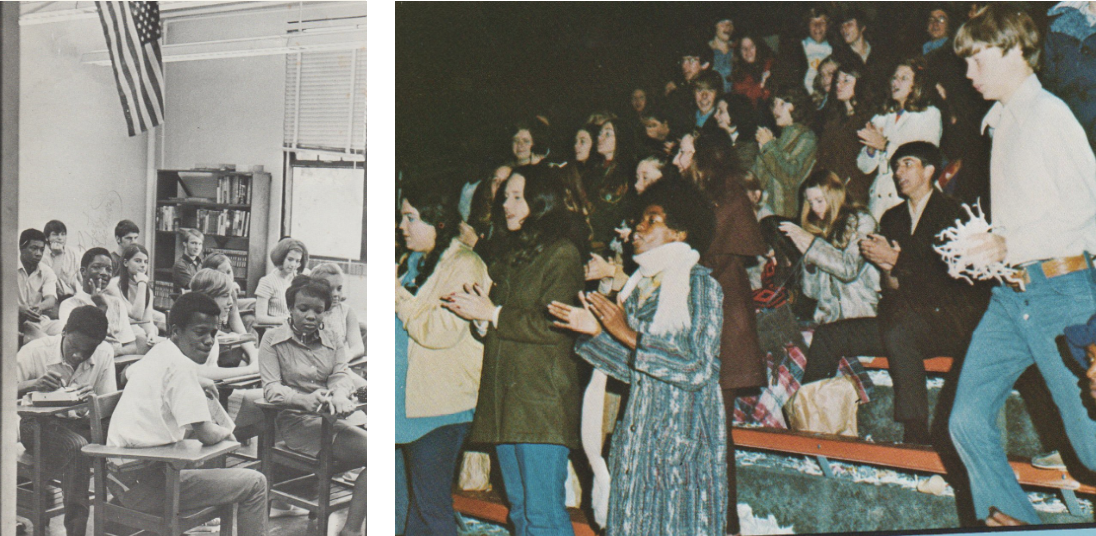

From the time Jackson High and Merry High merged to become the first fully integrated school in Jackson to the sad closing of a school that was a shell of its former self in 2016, JCM was a Jackson fixture — a school that embodied hope at its highest point and abject sadness at its closing. Each person who walked the halls of the West Campus or East Campus has their own story. They all make up what JCM was and what JCM will be once again.

To understand most stories, the beginning is the most logical place to start. But to understand JCM’s journey, it is best to start at the end.

In May of 2016, JCM saw its last graduating class leave the building. By that time, enrollment had dropped by nearly 75% from two decades prior when my class of 1997 walked out of Oman Arena with our degrees in hand. The physical campus had also been cut in half from two decades prior with Madison Academic inhabiting what used to be the west campus. Another magnet school, Liberty Tech, had further diluted the student population when it opened in 2003, leaving JCM with only 600 students during the last year of its existence.

Along with the disappearance of actual student bodies, the diversity of JCM had also vanished. The exponential growth of private schools and what truthfully amounted to legal resegregation in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s had been too much for JCM to overcome while trying to maintain any semblance of diversity — racial or socioeconomic. Ironically, the beginning of JCM’s story and what it came to represent in Jackson was the first step toward mending generations of racial strife and inequities.

In 1970, Jackson High and Merry High merged to become Jackson Central-Merry. While being close in proximity, the schools were very different before their merger. Students at Merry High would have to use hand-me-down textbooks that had been previously used by the white students at Jackson High. The schools were released 15 minutes apart at the end of the day to prevent unnecessary interactions between the students. Today, Oman Arena casts a bulky shadow across the cracking parking lot separating the two schools, but before 1967 only open air lay between Jackson High and Merry High. Students from each school could visually see students from the other school, but social exchanges rarely occurred.

The symbolism of JCM combining two segregated schools to create a fully integrated school in 1970 is both heavy and obvious. What JCM grew to become, particularly after consolidation in 1992, had to have been close to what an idyllic version of de-segregated education looked like to the Civil Rights leaders who fought for educational equity. The importance of the physical location of JCM, however, is often overlooked.

Something that has always interested me is the way residential architecture changes as I travel north in Jackson from downtown. I live in midtown in a craftsman home built in 1930. There are many similar homes to mine in shape and design with sprawling front porches and deceptive space that stretches into each backyard of the homes in both midtown and East Jackson. As I drive toward the bypass by way of Russell Road, though, I can see the influence of mid-century modern architecture and trace the migration of developers and homeowners throughout the years. It’s no secret today that the northwest portion of our town is where the most economic growth is occurring. Subdivisions with accompanying cul-de-sacs seem to pop up overnight. Chain restaurants and national stores fill The Columns. The three major private schools form a triangle within one mile of each other. With this socio-economic migration, history and physical spaces become even more important to sections of town where development has been stalled for years.

In 2003, two new magnet schools opened in Jackson, striking a big blow to the student population of JCM. Madison Academic opened on what was formerly the West Campus of JCM. Over the next few years, many of JCM’s students elected to go to Madison. More of JCM’s students left to attend the newly built Liberty Tech Magnet School that was only five miles east of JCM. Moreover, USJ had consolidated its lower school and upper school on the same campus for the first time. Trinity Christian Academy would break ground on a brand new campus just two years later only a mile away from USJ. With the migration north to private schools and Medina, JCM’s student population continued to dwindle.

By its final year, the value of JCM had shifted. On a macro level, JCM had always been important to the Jackson community as a whole. In 1996, the girls basketball team won the 5-A Tennessee state basketball championship. The football program produced over twenty Division I college athletes and two NFL players. The baseball team produced multiple college athletes and one player who made it to the big leagues. JCM also produced a Harvard attendee as well as multiple National Honors Society Students. In short, JCM was well known throughout the city and the region.

The true value in JCM, however, has been the physical space it occupied in East Jackson.

My daughter lives in a suburb of Dallas and is in the eighth grade. She walks to her middle school each day. Beginning in the third grade, she also would walk to her elementary school. Neighborhood schools are much more than physical structures where learning takes place. They are staples of a neighborhood. They are conveniently located to limit the amount of time and gas it takes to get a student to school. They are even more important in communities where time and money need to be stretched.

What JCM meant to midtown and East Jackson is very difficult to quantify. There was an inherent pride in being a Cougar and being within walking distance to go see a basketball game at the Oman Arena or walk to Rothrock to see a football game on a Friday night.

In other ways, however, the closing of the school had very real consequences. When JCM closed in 2016, the students were affected, but so was the neighborhood and the families who had to take their children to school or put them on a bus to be transported to Liberty or South Side. This put a strain on some of the most vulnerable families in our city. Not only did they lose a neighborhood school and the extracurricular activities that accompanied it, but students also faced long bus rides or parents had to make arrangements to get their students to school on time while also getting to work on time themselves. When those doors finally shut in May of 2016, the impact was felt in the neighborhood.

In most contexts, the words evolution and resurrection stand in stark contrast to one another. Evolution is a means for survival — adapting to situations through growth and change to arrive at a place that’s different but necessary. The word resurrection implies some sort of ending or death and then a resuscitation and a new life following it. It’s a phoenix rising from the ashes or a stone rolled away from a tomb. It’s mythological but also hopeful. It can be argued that JCM is both evolving and being brought back from the dead. Either way, there is hope for what is next.

In the fall of 2019, conversations began about needing new schools — Pope in the northwest quadrant, Madison in midtown, and JCM once again became part of the discussion. Through complicated public/private partnerships, and even help from the city, plans were made to once again have JCM open and re-establish itself as part of the East Jackson community.

When students walk through the doors in the fall of 2021, their JCM won’t be my JCM. It will only be one campus, and will house middle school students as well as high school students. It won’t have a student population of 2,000 kids or the diversity of the mid 90’s. But there will be some similarities. JCM will once again have an athletic program. There will be a band and a theater department. There will be art classes and all the core academic subjects. There will be green and gold again. There will be a school for the neighborhood once more, and that is why JCM will continue to be impactful in our community.

Just as Jackson has evolved and shifted over time, so has Jackson Central-Merry. As the school embarks on this different version of itself, the importance of what it means and what it has meant must not be forgotten or overlooked. This JCM can be an anchor in East Jackson. It can be a partner with Lane College. It can provide an education for kids in their own neighborhood without having them scattered to South Jackson or Northeast Jackson. It can provide hope and community and instill a sense of pride.

I live within a mile of what was the West Campus of JCM when I attended school there. A few weeks ago, another former JCM student and I walked to the campus to see what it would feel like. We walked through the parking lot and peeked through the doors. We saw the crosswalk bend and disappear beyond North Royal just like it did nearly 30 year ago. We shared our own memories of our personal experiences there, and I knew that everyone who ever attended JCM had their own version of its history. All of our stories combined to tell the story of that school. We were all shaped in some way by the teachers or friends or coaches we encountered during that most sensitive time of life.

In August, another generation of Cougars will start to have their own memories seared into their conscious minds. Some of those will fade over time, but some will stick indiscriminately just as mine did. These students will be telling their children about their first day at JCM, and JCM will have added multiple chapters to its story. Its story is all of our stories. In a way, we are all JCM because just as we’ve been shaped by Jackson and its evolution, so has this school. And just like us, it continues to be grown and shaped by our town.

GABE HART is an English and Language Arts teacher at Northeast Middle School. He was born and raised in Jackson, graduating from Jackson Central-Merry in 1997 and Union University in 2001. Gabe enjoys spending time and traveling with his daughter, Jordan, who is eight years old. His hobbies include reading, writing, and playing sports, even though he’s getting too old for the last one. Gabe lives in Midtown Jackson and has a desire to see all of Jackson grow together.