Unsung History: Gil Scott-Heron's Jackson Roots

By Gregory D. Hammond

“who say to the seers, “See not,” and to the prophets, “Prophesy not unto us right things; speak unto us smooth things; prophesy deceits.” Isaiah 30:10

It’s possible Gil Scott-Heron is the most notable Jacksonian you’ve never heard of. If you are familiar with Gil’s life and legacy as one of the nation’s preeminent bluesologists, there’s a good chance this was revealed to you fairly recently. That’s because his 2021 induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, as well as his 2012 and 2014 Grammy Awards, have produced a very strange and curious question. How does a town that prides itself on strong musical heritage go decades without celebrating one of its most notable connections?

My knowledge of Gil Scott-Heron came about through my work in sports media and education. In short, it was a fluke. In truth, I should have learned about Gil the same way I learned about other musicians and music from the 1960’s and 70’s — on the local oldies station. It’s a curious situation, in reflection, that a kid in Jackson could hear Eric Clapton sing about the robust uses of Cocaine and never once hear Gil’s soulful warning against drug use in his 1978 single Angel Dust; even though it was considered one of his most commercially successful tracks.

Heron by Happenstance

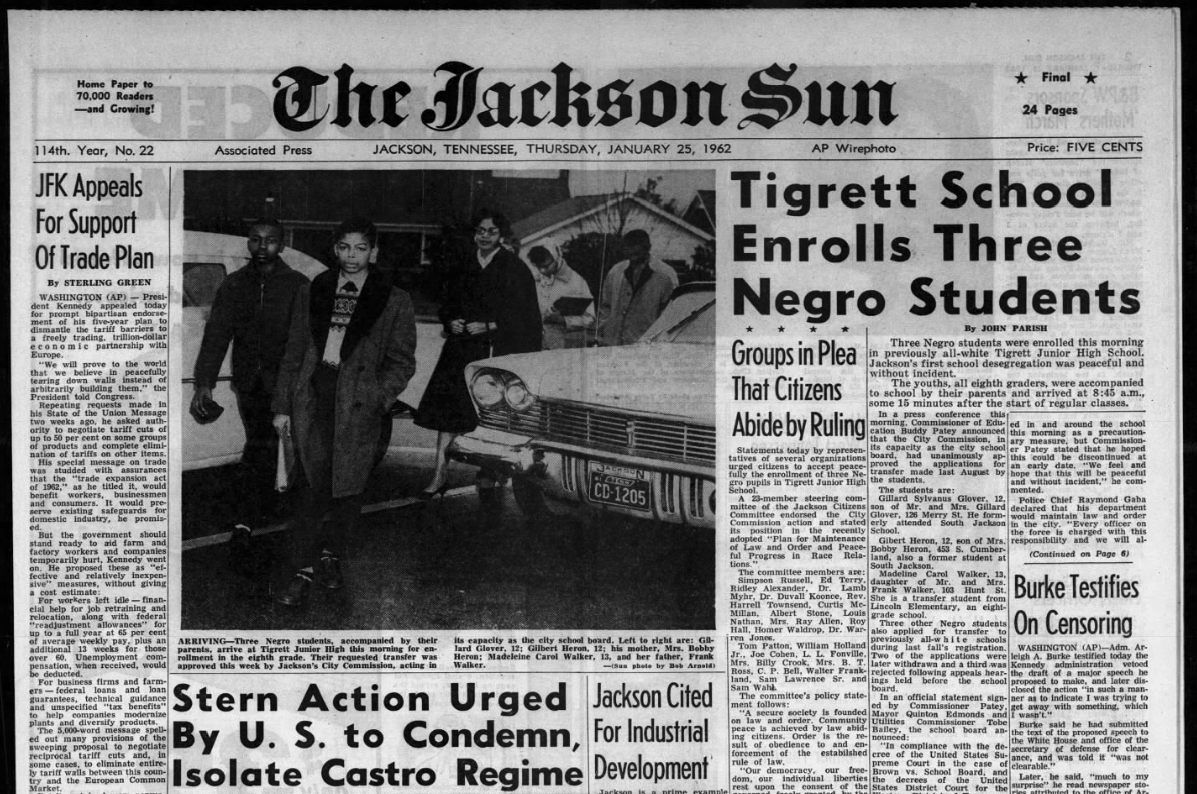

I was 35, as it happened, when I interviewed Buddy Patey a second time. Our first conversation centered around his decades-long experience as a college football official. The second interview was about Mr. Patey’s tenure as the Commissioner of Health, Education, Sanitation, and Recreation for the City of Jackson. He oversaw desegregation in the public school system. The late city leader was describing the lead-up to three young African-American teens integrating Tigrett Jr. High in 1962: Madeline Walker, Gil Scott Heron, and Gillard S. Glover. He explained that Gil’s father had been a very famous soccer player in Europe, and that Gil had become quite famous as a poet and jazz musician. I began to research information on Gil a few weeks later.

Say it Loud

Gil Scott-Heron was born in 1949 which put him in a generation of Black Americans who were able to say and do things African-Americans had not previously been allowed to say or do in the land of the free; things Black Americans were arrested, beaten or even murdered for attempting: voting; enjoying public accommodations; attending a neighborhood school; having an opinion; speaking up for themselves. As Gil would say, “you get the picture.” Gil used his talents in music, poetry, and awareness of culture to share his opinions — via music — on government policy (“No Knock” 1979), consumerism (“The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” 1971), poverty and violence (“Gun” 1981), economic inequality (“Whitey on the Moon” 1970) and racial segregation (“Johannesburg” 1990) and much more. A review of his music today, void of context, would likely get him canceled. But considering that a kid in Jackson could listen to the local oldies station in the 1990’s and never hear a Gil Scott-Heron song suggests Gil and many of his contemporaries were canceled decades before cancel-culture went mainstream. This canceling has been to the detriment of local arts and culture. But it doesn’t have to continue.

A Legacy to Celebrate

Gil Scott-Heron’s life provides a snapshot of contemporary American history that is both celebratory and sad; hopeful and yet unresolved. I would encourage any Jacksonian with the slightest interest in music, history, or culture to read Gil’s memoir The Last Holiday. It’s one of four books he published. Gil, a John Hopkins educated performer, writes in great detail about his time as a child in West Tennessee; growing up in South Jackson (not Bemis, but old South Jackson in the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive/South Cumberland Street area); attending St. Joseph’s (the former Catholic school in Jackson for Blacks), desegregating our public school system and much more. His celebrity in the musical arts would rise decades after he learned to play piano — in Jackson. Richard Pryor hand-picked Gil to serve as his musical guest on Saturday Night Live in December of 1975. Nearly half a decade later, when Stevie Wonder used music to assist the Black Caucus of the U.S. Congress to champion the cause of making Dr. King’s birthday a national holiday, Gil was recruited as the opening act of the national tour (hence the name of his book). Considered by many to be the Godfather of rap, Gil’s music spanned soul, jazz, funk, R&B. His public criticism of policies enacted by Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Alexander Haig and their contemporaries might play into the reason Gil’s fame is a bit obscure. Although critics will refer to Gil’s struggles with substance abuse as a detriment to his fame; we only need to refer to any number of Rock & Roll Hall of Famers to know that’s probably not the case. Gil’s ultimate flaw was his propensity for truth. In an industry that celebrates sex, drugs and rock & roll, there’s little demand for political commentary or calls for restorative justice; these aren’t smooth things. Cultural prophets are rarely celebrated.

Gil Scott-Heron 101

Just as Whitney Houston sang Dolly Parton’s I will Always Love You and made it her own, Gil’s rendition of songs by Bill Withers (“Grandma’s Hands” 1981) and Marvin Gaye (“Inner City Blues” 1981) are beautiful pieces of music; nearly original as he puts his own personality and experience on these works. It’s important to remember that not all of Gil’s music was political, taboo, or rough. Save The Children (1971), Is That Jazz (1981), and When You Are Who You Are (1971) should be in rotation on the airwaves of every R&B, adult contemporary, and oldies station in West Tennessee. They’re beautiful songs by a notable Jacksonian; a Rock & Roll Hall of Famer and local Civil Rights icon — Gil Scott-Heron. It’s a musical legacy worth celebrating.

Gil Scott Heron’s portrait hanging alongside Carl Perkins and Valerie June at Turntable Coffee Counter.

Greg D. Hammond serves the Jackson-Madison County School System as Chief of Public Information. Prior to joining district leadership, Greg taught Broadcasting at South Side High School, his alma mater, for 12 years. He has worked in television, radio and newspaper since graduating from South Side and the University of Tennessee at Martin. Greg is married to former Union University softball standout Megan Quarry. Their two children are students in the public school system.